On the shelf

Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant: A Memoir

By Curtis Chin

Little, Brown: 304 pages, $30

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.orgwhose fees support independent bookstores.

It was the 1980s and Detroit was dealing with civil unrest, the AIDS crisis, crack cocaine, and massive racial tensions. Curtis Chin was just a child when a close family friend, Vincent Chin, murdered by racist auto workers. By the time Chin turned 18, violence in his hometown had claimed the lives of five people he knew.

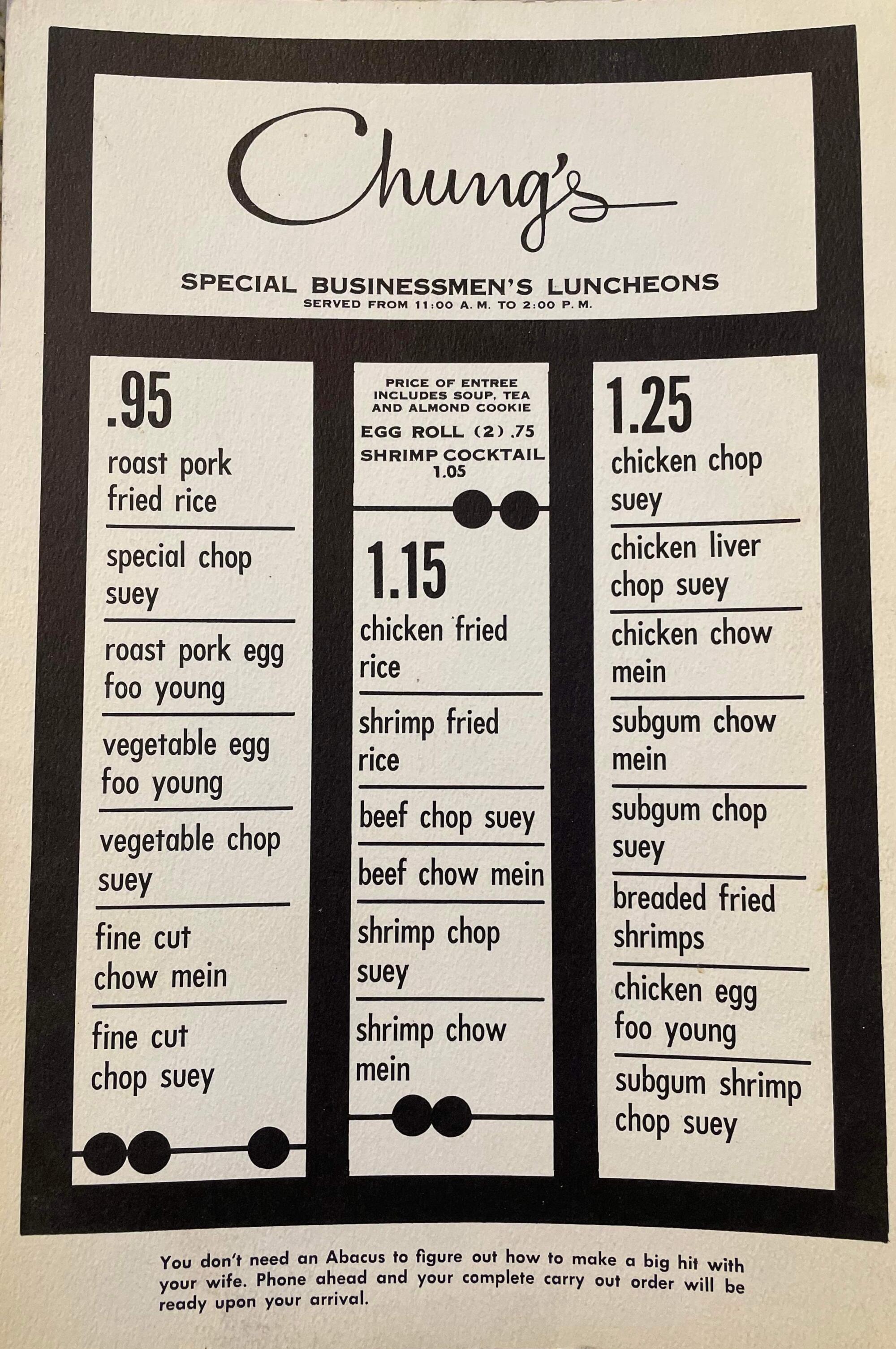

But Chin’s family restaurant, Chung’s, was an oasis Cass Corridor where everyone was welcome to feast on American Chinese food: drug dealers, sex workers, gay men, Broadway touring artists, even Detroit’s first black mayor. At its peak, Chung’s sold 4,000 egg rolls a week.

“We were the oldest surviving Chinese restaurant” in Detroit, Chin said in an interview last month about the release of his new memoir.Everything I learned, I learned in a Chinese restaurant.” His parents, who did not graduate from college, encouraged Chin and his siblings to learn from everyone who walked through their doors. “Every time my dad met someone who had a cool career… he’d call all six of us and we’d run and barge [them] with all these questions.”

Three generations of Chins faithfully maintained the establishment from its inception in 1940 until the restaurant officially closed in 2000. With no restaurant to go by, Chin began writing stories to share with his nieces and nephews about their family history — stories that became his memoirs. In bite-sized chapters referred to as menu items, he examines his upbringing as a queer Chinese-American child learning to find his place.

It was not as easy as it seems now. Chin, 55, worked for years as a community writer and storyteller, becoming the first head of the Asian American Writers Workshop, advising the Democratic Party on the promotion and creation of feature films and documentaries. But it took him a decade to find a home for a book he had written himself.

The lunch menu at Chung’s, Curtis Chin’s family restaurant in Detroit.

(By Curtis Chin)

It was “a different memoir” at first, Chin explained, “focused on my high school years as a kid. It was just crazy stories about my grandma and grandpa running the Chinese mafia.”

It was the COVID pandemic that pushed the book in a different direction. As anti-Asian hate crimes increased and the killing of George Floyd sparked a nationwide movement against racism and police brutality, Chin turned to contemporary issues and the memoir suddenly became relevant. After a three-week bidding war, Little, Brown broke it down to a six-figure contract.

“I hope the book opens a conversation and brings people together,” Chin said. “As I’ve joked before, the pitch is: Come for the egg rolls, but stay to talk about racism.”

Chin was a staunch Republican in high school and even college before migrating to the Democratic Party. He later went on to advise the Obama campaign on Asian American issues. He explains his past political affiliation as part of his own struggles for assimilation.

“One of the racist stereotypes against Asian Americans is that we’re not very loyal to the US, right?” Chin said. “To fit in, I tried to go to extremes. So, I tried to outdo my classmates.”

Curtis Chin is the author of Everything I Learned I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant.

(Michelle Lee / Studio Plum Photography)

Chin may seem like a literary late bloomer, but those who have benefited from his activism are not surprised by his latest series. Jeff Kim, Chin’s partner for more than three decades, has seen his husband consistently champion Asian American stories throughout his career.

“He has this network of goodwill,” Kim said. It goes all the way back to Michigan State University, where Chin studied poetry before moving to New York and co-founding AAWW in 1991. That group provided a safe space for AAPI writers in New York, Kim explained, at one point. when racist and fetishistic depictions of Asians were still prevalent in the arts.

When Chin followed Kim to Los Angeles in the late 1990s, he couldn’t find a nonprofit position in the arts, so he turned to writing for network and cable television. He eventually made a documentary focusing on the heritage of Asian American figures. his most recent film, “Dear Corky,” follows the work of Asian community photographer Corky Lee. And he had production responsibility for the 2008 documentary “Vincent Who?,” which brought renewed awareness to his friend’s murder decades ago.

Now, after helping launch so many careers, it’s Chin’s turn in the spotlight.

The memoir feels less like a career change than an extension of his life’s work. “The book is perennial or universal,” he said, “because of some of the issues we face as Asian Americans… the idea that we’re outsiders, the idea that we’re dirty, the idea that we don’t assimilate—these are all things that have followed us from the when our ancestors first came, they have not changed. The only thing that has really changed is our ability to respond to these issues and be able to push back.”

Chin’s family at their restaurant. From left, father, mother, sister Cindy, brother Clifford and grandfather Tom.

(By Curtis Chin)

Chin’s background as an organizer came in handy when it came time to plan his book tour. He scheduled 30 community readings before his book was even officially released, supplementing his publisher’s budget with institutional funding through speaking engagements with Asian American community groups, universities, and museums.

It’s not just about his own success, Chin said. “If the book doesn’t sell, then it becomes a challenge for us in the long run as writers of color. That’s why I’m doing everything I can to make sure this book is a bestseller.”

Healthy sales would also give Chin the chance to publish a follow-up to his memoir with all the stuff he left out — and there’s a lot. There was the experience of moving to New York and becoming an activist in the thick of the AIDS crisis. And there’s the story — which he’s not “emotionally ready” to tell — about the car accident that killed his father and led to the sale of Chung’s. What he doesn’t want to do is write another chronological story explaining how he reconciled with his family.

“Every queer person knows, the process of ‘coming-out’ is not a simple act,” Chin said. “It’s something we do all the time, no matter how old we are.”

For now, Chin is content to soak up Los Angeles in all its richness, particularly the Asian American enclaves of Koreatown, Little Tokyo and the San Gabriel Valley—when he’s not making annual jaunts to London. Asked if he’s here to stay, he jokes that he’s in Detroit, Los Angeles and London.

Wherever he goes now, home will feel as close to him as the nearest Chinese restaurant, his lifelong class and a testament to the resilience of his family and Asian immigrants everywhere.

“We’ve always, you know, fought hard,” he said. “The odds have always been against us, but we just persevere. And that’s all you can do.”